Written by Student Sherine Huballah, ID: GP95376 Global Affairs Department, Cuttintong University School of Graduate and Professional Studies.

Introduction

International legal instruments protecting women have evolved significantly since the mid-20th century, establishing women’s rights as integral to human rights. These instruments address discrimination, violence, political participation, economic equality, and reproductive rights, aiming to achieve gender equality worldwide. They include binding treaties (conventions) that obligate ratifying states to implement changes, as well as non-binding declarations that set global standards and influence policy.

These instruments collectively obligate states to enact laws, provide remedies, and promote equality. While progress has been made, such as increased ratifications and national reform challenges persist in implementation, enforcement, and addressing emerging issues like digital violence. They remain vital tools for advocates pushing for systemic change toward gender equality. International legal instruments protecting women form a comprehensive and evolving framework aimed at eliminating discrimination, preventing violence, and ensuring equality in all spheres of life. While significant progress has been made, effective protection depends on state implementation, political will, and enforcement mechanisms. Strengthening domestic incorporation, monitoring, and accountability remains essential to transforming these legal commitments into lived realities for women worldwide.

Why Specific Legal Protections for Women Exist

Legal protections targeted at women, through international instruments like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and regional conventions, are not about granting “special privileges” but about addressing systemic, historical, and ongoing gender inequalities that disproportionately affect women and girls. Gender equality requires eliminating discrimination based on sex, and because women have faced (and continue to face) structural barriers rooted in patriarchy, culture, and power imbalances, neutral laws alone often fail to achieve true equality. Protection aim to level the playing field, promote substantive equality, and fulfill human rights obligations.

For centuries, women were legally subordinated:

Denied voting rights, property ownership, and legal independence (e.g., under coverture laws, married women were treated as extensions of their husbands).

Excluded from education, employment in certain fields, and political participation.

Subject to practices like child marriage and female genital mutilation in many societies. In essence, these protections aim for substantive equality, leveling the playing field, rather than formal identical treatment, supported by evidence of ongoing disparities in violence, pay, and opportunities. Many laws now trend gender-neutral (e.g., parental leave), but woman-specific ones persist where differences justify them.

The United Nations Charter (1945) and Its Role in Protecting Women

The Charter of the United Nations, signed on 26 June 1945 in San Francisco and entering into force on 24 October 1945, is the foundational treaty establishing the UN. It represents the first international agreement to explicitly affirm gender equality as a fundamental principle, marking a pivotal starting point for international legal instruments protecting women’s rights.

While the Charter is a general document focused on peace, security, and human rights rather than a specialized women’s rights treaty, it laid the essential groundwork. It explicitly mentions equality between men and women multiple times, influencing subsequent dedicated instruments like CEDAW (1979).

Article 1(3):

Establishes the promotion and encouragement of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms “for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

Article 55(c):

Calls for universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms without distinction as to sex.

These provisions mark one of the earliest international recognitions of gender equality as a legal principle. The United Nations Charter (1945) plays a foundational and enduring role in protecting women by embedding equality, human rights, and non-discrimination into international law. While it does not explicitly address women’s issues, it provides the legal and institutional framework upon which all subsequent international women’s rights instruments are built. Its continued relevance underscores the centrality of gender equality to global peace, development, and justice.

Key Provisions on Gender Equality

Preamble: Reaffirms “faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.”

Article 1(3) (Purposes of the UN): Promotes “respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

Article 8: “The United Nations shall place no restrictions on the eligibility of men and women to participate in any capacity and under conditions of equality in its principal and subsidiary organs.”

Article 55(c): The UN shall promote “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and Its Role in Protecting Women

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (Resolution 217 A), is a milestone document in the history of human rights.

Drafted in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, it sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected. While not legally binding (unlike later treaties), it has profoundly influenced international law, national constitutions, and subsequent human rights instruments, serving as a “common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations.”

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995)

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted on 15 September 1995 at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, is widely regarded as the most comprehensive and progressive global agenda for advancing women’s rights and achieving gender equality.

Article 1(3):

Establishes the promotion and encouragement of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms “for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

Article 55(c):

Calls for universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms without distinction as to sex.

These provisions mark one of the earliest international recognitions of gender equality as a legal principle.

These provisions mark one of the earliest international recognitions of gender equality as a legal principle. It built on previous UN efforts, including the UN Charter (1945), UDHR (1948), and CEDAW (1979), but shifted focus to practical, strategic actions. Though non-binding, it has served as a powerful blueprint, influencing laws, policies, and advocacy worldwide. It marked the 50th anniversary of the UN and built on prior world conferences (e.g., Nairobi 1985). A landmark moment was U.S. First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton’s speech declaring, “Women’s rights are human rights, and human rights are women’s rights,” which galvanized global attention and challenged cultural relativism on issues like violence against women.

The Declaration and Platform were adopted by consensus, committing governments to equality, development, and peace for women. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action remain a cornerstone of global gender equality efforts. Although not legally binding, its comprehensive vision and detailed commitments have shaped international norms and national policies for nearly three decades. Its continued relevance underscores that achieving substantive equality for women requires sustained political will, accountability, and inclusive participation.

Key Elements

Beijing Declaration: A political statement of commitment by governments to advance women’s equality, recognizing obstacles like poverty, violence, and lack of power.

Platform for Action: The core document outlining 12 critical areas of concern with strategic objectives and specific actions for governments, international organizations, NGOs, and the private sector.

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000)

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325), adopted unanimously on 31 October 2000 during the 4213th meeting of the Security Council (presided over by Namibia), is a landmark binding resolution on Women, Peace and Security (WPS). It was the first formal UN Security Council document to explicitly link women’s experiences in conflict to the maintenance of international peace and security, recognizing both the disproportionate impact of war on women and girls and the critical role of women in conflict prevention, resolution, and peacebuilding.

Significance of Resolution 1325

First UN Security Council resolution to link women’s rights with international peace and security.

Shifted women from being seen only as victims to agents of change.

Laid the foundation for the Women, Peace and Security agenda, followed by subsequent resolutions (e.g., 1820, 1888, 1889, 2242).

Implementation Mechanisms

National Action Plans (NAPs):

Member States are encouraged to adopt NAPs to implement 1325 domestically.

UN Peace Operations:

Gender advisers and gender mainstreaming are mandated in missions.

Reporting & Accountability:

The UN Secretary-General reports regularly on progress and challenges

The Maputo Protocol (2003)

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, commonly known as the Maputo Protocol, was adopted on 11 July 2003 in Maputo, Mozambique, by the Assembly of the African Union (AU). It entered into force on 25 November 2005 after receiving the required 15 ratifications. Widely regarded as one of the most progressive regional treaties on women’s rights globally, it supplements the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981) by addressing gaps in women’s protections and tackling issues specific to the African context. The Protocol supplements the 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which lacked sufficient gender-specific provisions. It addresses systemic discrimination, harmful traditional practices, and vulnerabilities faced by women in Africa, aiming for substantive equality by recognizing biological, historical, and social factors that disproportionately affect women. This aligns with broader efforts to remedy inequalities in political participation, health, violence, and economic opportunities.

Key Challenges

- Implementation and Enforcement Gaps

These instruments often lack strong binding enforcement mechanisms. States ratify treaties but fail to translate obligations into domestic law or practice due to insufficient monitoring, accountability, or sanctions. - State Reservations and Declarations

Many states enter reservations to core provisions, particularly on family law, equality in marriage, and cultural/religious practices. - Lack of Political Will and Resources

Governments frequently lack commitment due to competing priorities, inadequate funding, or resistance to challenging power structures. - Cultural, Societal, and Patriarchal Resistance

Deep-rooted norms, stereotypes, and patriarchal attitudes perpetuate violence and inequality. - Emerging and Intersectional Issues

New forms of violence, such as digital/cyber harassment, deepfakes, and online abuse, outpace existing frameworks, with nearly half the world’s women lacking legal protections. - Backlash and Regression

Rising anti-gender movements challenge gains, leading to defunding of women’s organizations, restrictive laws, and rollbacks on reproductive rights or violence protections.

Conclusion

International legal instruments protecting women represent a major achievement in the evolution of human rights law. From the foundational principles of equality in the UN Charter and UDHR to the detailed and transformative provisions of CEDAW and regional treaties, the international community has recognized that women’s rights require specific legal attention and protection.

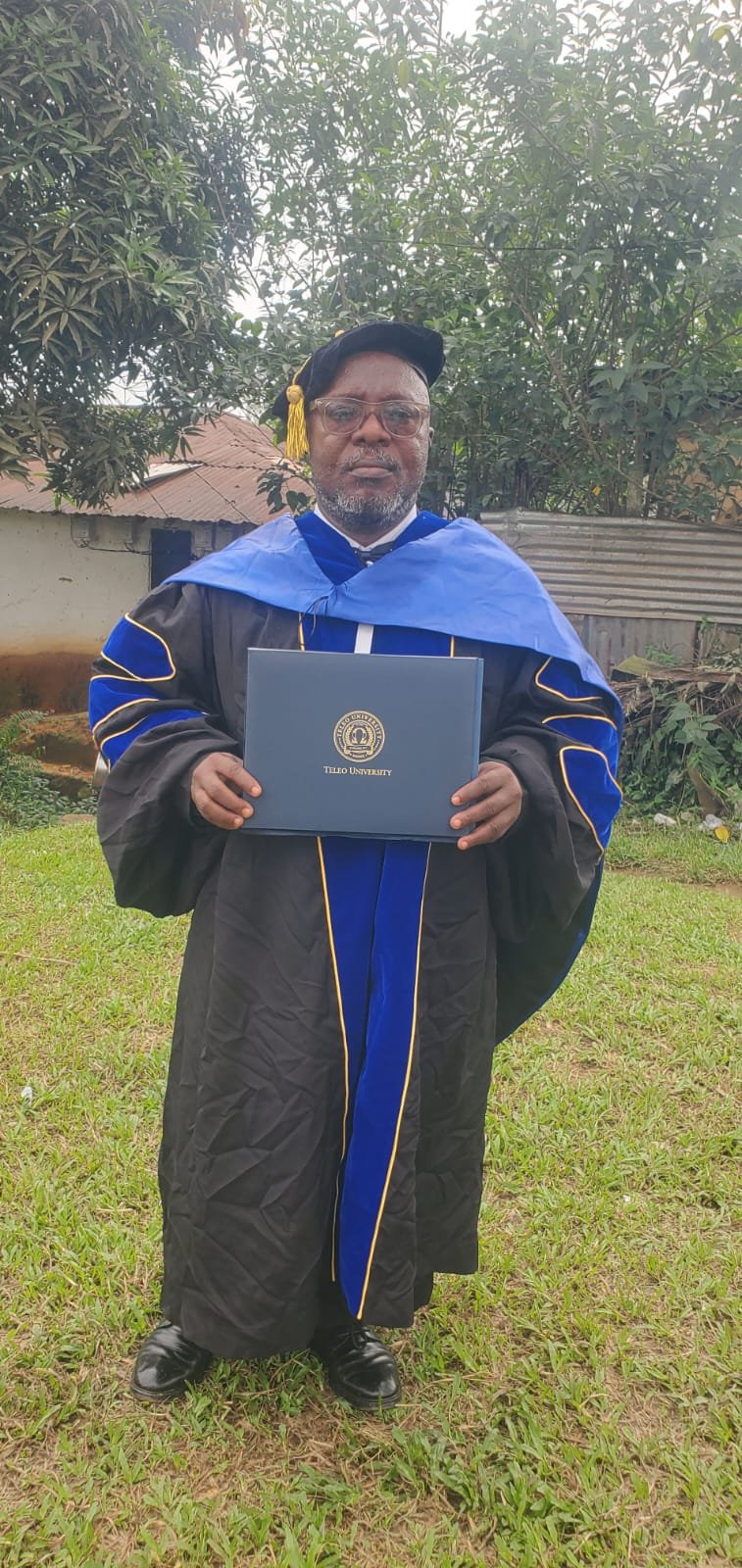

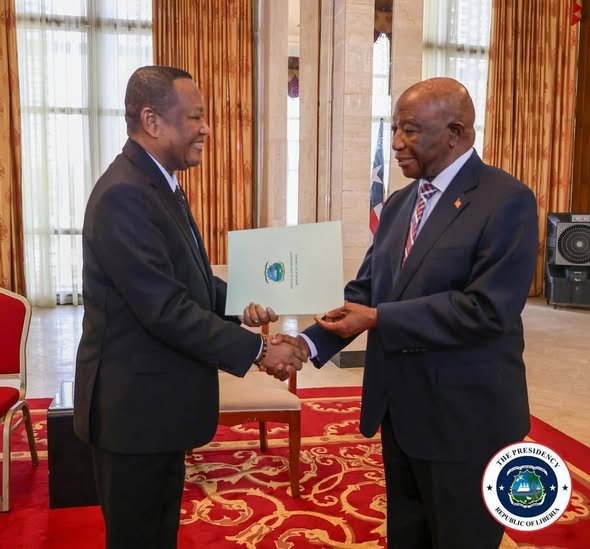

This essay was part of the International Law Course taught by Dr. Mory Sumamoro (Ph.D.), Professor at the Cuttington University Graduate School of Global Affairs and Policy.

References

African Union. (2003). Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol). African Union.

Belém do Pará Convention. (1994). Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women. Organization of American States.

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. (1999). Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. United Nations.

Cook, R. J. (1994). State responsibility for violations of women’s human rights. Harvard Human Rights Journal, 7, 125–164.

Fredman, S. (2011). Discrimination law (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

United Nations. (1945). Charter of the United Nations. United Nations.

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations.

United Nations. (1966a). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. United Nations.

United Nations. (1966b). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations.

United Nations. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). United Nations.

United Nations General Assembly. (1993). Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (A/RES/48/104). United Nations.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2014). Women’s rights are human rights. United Nations.